For many e-commerce teams, Google Ads tROAS eventually becomes a ceiling rather than a guardrail. Accounts look “efficient” on paper – ROAS is high and CAC is controlled.

Yet revenue stalls, impression share is capped, and growth conversations quietly turn into budget reallocation debates. The store isn’t losing money — it just isn’t moving fast enough.

This is where decreasing tROAS can unlock profitable growth, not despite lower efficiency, but because of it.

This article explains why that works, when it doesn’t, and how to apply it in a way that respects ecommerce unit economics, cash flow, and real Google Ads behavior.

The Hidden Cost of Chasing a High ROAS

High ROAS feels safe. It signals discipline, efficiency, and control. But in Google Ads, a high tROAS often comes with trade-offs that are easy to miss.

When you push tROAS too high, you force the algorithm to:

- Prioritize only the highest-intent, lowest-volume queries

- Avoid marginal auctions entirely

- Underbid in competitive placements

The result is predictable:

- Strong efficiency metrics

- Flat revenue

- No room to grow your online store further

ROAS optimization, taken too far, turns into demand harvesting, not demand scaling.

What tROAS Actually Controls in Google Ads

Before talking about lowering target ROAS, it’s important to understand what it does.

Target ROAS optimizes for revenue efficiency per euro spent, based on historical signals. When you raise it, you’re telling Google:

“Only spend where revenue per click is highly predictable and safely above average.”

When you lower it, you’re saying:

“I’m willing to accept lower immediate efficiency to access more volume.”

That volume includes:

- New auctions you previously skipped

- Broader query sets

- Less obvious buyer journeys

- Higher CPCs that were previously filtered out

None of that is inherently unprofitable. It’s just less predictable.

Why Lower tROAS Can Still Mean Positive Unit Economics

The key mistake is equating lower ROAS with negative contribution margin.

What matters is not ROAS in isolation, but whether incremental spend still clears your unit economics.

A simplified framing many teams use in practice:

- If contribution margin after COGS and variable costs is healthy

- And incremental CPA stays below that margin (read: positive contribution margin)

- Then growth remains profitable, even at lower ROAS

In other words, you don’t need a “great” ROAS. You need acceptable margins.

This distinction is critical when thinking about how to scale an ecommerce business.

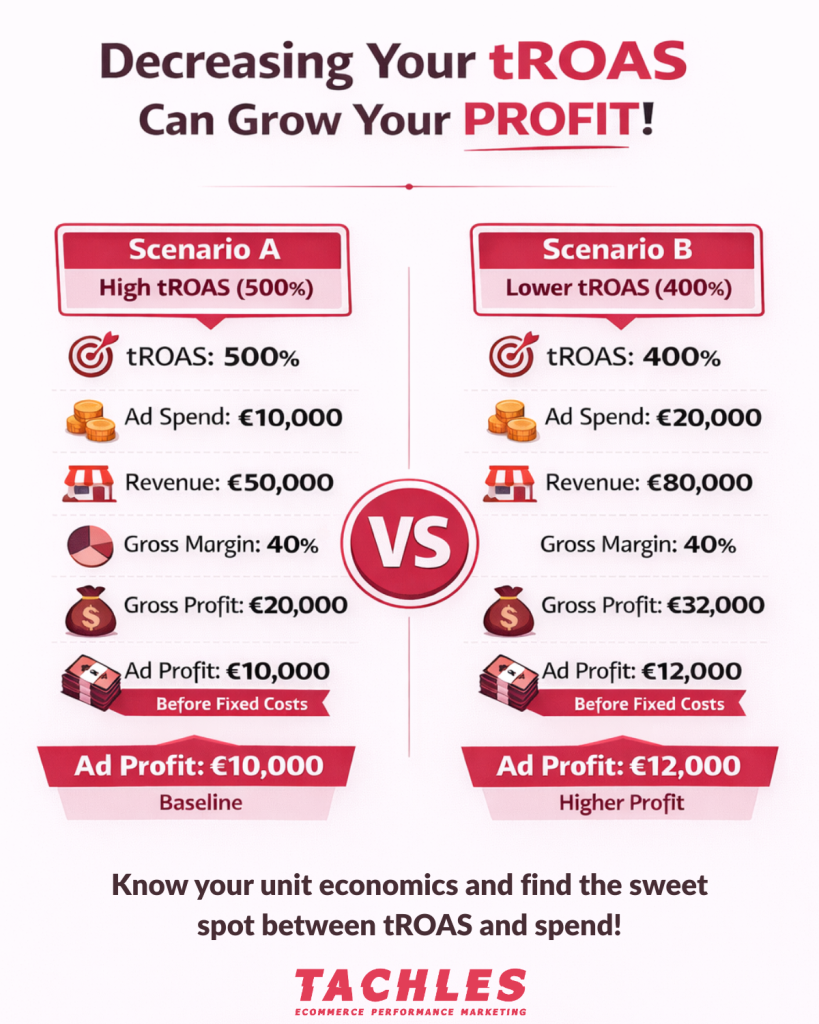

A Practical Example: Efficiency vs. Absolute Profit

Consider a DTC brand running Google Ads profitably but slowly.

Scenario A: High tROAS, capped scale

- tROAS: 500%

- Spend: €10,000

- Revenue: €50,000

- Gross margin: 40%

- Gross profit: €20,000

- Contribution after ads: €10,000

The account looks excellent. But spend can’t increase without breaking the ROAS target.

Scenario B: Lower tROAS, higher volume

- tROAS: 400%

- Spend: €20,000

- Revenue: €80,000

- Gross margin: 40%

- Gross profit: €32,000

- Contribution after ads: €12,000

Efficiency dropped, but revenue grew significantly and contribution margin improved!.

But that’s not all – let’s look at the other benefits scale unlocks.

The Second-Order Effects ROAS Doesn’t Show

Lowering tROAS often unlocks benefits that don’t appear in standard Google Ads columns.

1. Fixed cost dilution

Most e-commerce operations carry fixed or semi-fixed costs:

- Team salaries

- Tools and software

- Creative production

- Warehousing overhead

More revenue spreads these costs thinner. Even if ad efficiency declines slightly, operating margin can improve.

2. Customer mix expansion

High tROAS strategies tend to over-index on:

- Returning customers

- Brand-heavy queries

- Bottom-funnel behavior

Lower tROAS allows more exposure to:

- First-time buyers

- Less price-anchored users

- Discovery-driven journeys

These customers often look “worse” on day-one ROAS but perform better over time. However, brands with good retention will see LTV improvement over time.

3. Better learning for the algorithm

Constrained bidding limits data. Lower tROAS increases conversion volume and thus signal richness.

In many accounts, this improves bidding stability over time, even if short-term ROAS dips.

When Lowering Target ROAS Fails (And Why)

Decreasing tROAS is not a growth hack. It fails in predictable situations.

Common failure patterns include:

- Thin gross margins with little room for error

- No repeat purchase behavior (AOV = LTV)

- Long payback periods without sufficient cash buffer

- Operational bottlenecks that break under higher volume

In these cases, efficiency matters more than scale. Lower ROAS simply accelerates losses.

This is why ecommerce unit economics must be understood before touching tROAS.

How to Decide If You Should Lower tROAS

Before adjusting anything, pressure-test your fundamentals.

Ask:

- What is our true contribution margin per order, before marketing?

- How much inefficiency can we absorb short-term?

- Do we want more revenue, more customers, or more profit right now?

- Can operations handle higher order volume?

If the answers aren’t clear, lowering tROAS is premature.

A Controlled Way to Lower tROAS in Google Ads

Blindly reducing tROAS across the account is risky. Google Ads marketers usually approach this incrementally:

- Lower tROAS on non-brand or high-volume campaigns first

- Leave brand campaigns untouched

- Adjust in steps (e.g. 10% at a time – frequency depends on conversion volume)

- Observe marginal CPA and revenue growth, not just blended ROAS

Key metrics to watch:

- Incremental spend vs. incremental revenue

- Contribution margin, not ROAS alone

- Conversion volume stability

- Impression share growth

The goal is not to “accept bad performance,” but to buy more of the performance that is still economically sound.

How This Fits Into Scaling an Ecommerce Business

For brands asking how to scale an ecommerce business, this is often the missing lever.

Early Stages Reward Efficiency. Expect More Variance at Scale

In early-stage or smaller e-commerce accounts, efficiency is survival: Budgets are tight, cash flow is critical, and a few bad weeks can really hurt the business.

At this stage, high ROAS protects downside risk. You intentionally avoid uncertain traffic because variance (swings in CPA or ROAS) can be dangerous.

As a brand grows, the situation changes: Budgets are larger, cash buffer exists, and the business can take a few bad weeks. Now, variance becomes the cost of accessing more volume.

Scaling means entering auctions that are less predictable but collectively profitable. Lower variance tolerance caps growth.

Accepting Lower Averages

When you scale, you move from ‘only the best-performing clicks’ to the ‘best clicks plus the pretty good ones’.

Inevitably the average drops.

Example:

- First €10k spend captures the highest-intent demand

- Next €10k includes slightly weaker signals

- The average ROAS declines, but total profit can increase

Scaling requires accepting that the marginal euro is worse than the first euro, while still being economically rational. This is the law of diminishing returns.

Focus on Totals, Not Ratios

Ratios (ROAS, CPA, conversion rate) describe efficiency.

Totals (profit, revenue, customers) describe business impact.

At small scale: Ratios correlate strongly with business health.

At larger scale: Ratios can improve while the business stagnates; or worsen while the business grows profitably.

Example:

- 6.0 ROAS on € 5 k spend → small profit

- 3.5 ROAS on € 50 k spend → much larger profit

Optimizing ratios too aggressively often shrinks the pie to protect the percentage.

ROAS Is a Percentage. Growth Is Absolute

ROAS answers: “How efficient was each euro?”

Growth answers: “How much value did we create in total?”

A business does not pay salaries, inventory, or investors with ROAS – it pays them with cash generated in total.

At Some Point, Optimizing the Ratio Starts Hurting the Outcome.

There is a tipping point where: Further ROAS improvements reduce volume, which in turn limits total profit.

The account becomes “perfect” but small.

This is when ROAS optimization turns from a growth tool into a constraint.

The outcome suffers not because efficiency is bad, but because over-optimization prevents scale.

Note: Lowering tROAS does not mean ignoring profitability or spending aggressively without limits. It means accepting lower marginal efficiency where economics allow.

Bringing It Back to the Core Question

High tROAS protects efficiency, whereas lower tROAS unlocks volume. The art is knowing when to move between the two.

For many mature DTC brands, profitable growth doesn’t come from squeezing ROAS harder, but from loosening it carefully and letting the system work with more room.

Conclusion

ROAS is a control, not a destination.Lower tROAS can drive profitable growth to online stores when unit economics support marginal inefficiency, and when you have enough repeat purchases.

This should be tested carefully, by incremental changes and monitoring the outcomes – incremental top line revenue, customers and profit.